We take a stand for diversity as a condition for hospitable relations

By Fiorella Capasso,Fiodanice-Cultures en dialogue

February 2020

The value and methodological approaches that have developed throughout the history of the Congregation have been brought up to date thanks to the work of the International Justice and Peace Office and summarized in the 2018 Position Papers on Migration, Fighting Prostitution and Trafficking of Women and Girls, Protection of Minors and Youth, Integral Ecology and Economic Justice. They encourage all the realities committed to giving continuity to the charism and sustainability to the apostolic services to promote a new ethic that responds to the signs of the times with an old heart and new eyes: the different (but also the foreigner, the future, the unknown) should not be integrated but rather respected in his wish to live differently, to which corresponds, at the same time, our right to the specific singularity resulting from our own biography and culture of belonging: “There is nothing more radical than origin”[1].

Are we not faced, yesterday as now, with the invitation to “enter through the narrow gate” (Matthew 7:13-14) with all that follows in terms of increased need, for each partner of the mission, of “awareness that we ourselves need continual conversion” (Constitutions 4)?

How can we practice in a world so complex and compromised by the humanitarian drift, caused largely by the Western countries, one of the most widespread ethical and strategic principles witnessed by the life and work of St. Mary Euphrasia: “A person is of more value than the whole world”?

It is precisely in this perspective that the Italy-Malta Unit has endowed itself with a Strategic Plan that indicates the great challenges of the coming years “to get life back on track” and relaunch a mission capable of “responding more urgently to the cry of our wounded world”[2]. Inspired by the spiritual heritage of the Congregation, the Positions of the Congregation, the Magisterium of the Church and the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development promoted by the UN, the processes promoted by the Strategic Plan give way to complex collaborations from the point of view of the multitude of diversities called to confront each other and which, in some ways, ask to be “hosted” to generate the future together.

The restless times in which we live do not help: they are full of contrasts, of disorder, uprooting and accelerated movements that shake us, push us forward and often make us dizzy. In the globalized world, mobility and mixing of people, things and cultures cause tensions, confusions, uncertainties and existential and social changes that are whirling, unpredictable, disorienting.

The restless times in which we live do not help: they are full of contrasts, of disorder, uprooting and accelerated movements that shake us, push us forward and often make us dizzy. In the globalized world, mobility and mixing of people, things and cultures cause tensions, confusions, uncertainties and existential and social changes that are whirling, unpredictable, disorienting.

It also looks like the central feature of modernity is precisely the relationship of extraneousness.

It is understandable that, both in our daily relationships and as a result of complex world events, today we are often seized by bewilderment, dismay, fear. These days we find it hard to resist the desire to take refuge in the comfort of our own habits and/or in the illusion of mastering the encounter with diversity. We often prefer a position of domination (assimilation/expulsion) or a position of exclusion (indifference/separation). When diversity bursts in, we react automatically: as if one’s own experience and culture were inscribed in a common framework, which one believes is universally recognized – which the other would ignore/reject – but to which any differences should naturally conform.

These two positions, domination and exclusion, are deeply rooted in human dynamics. The inclination to project on the other thoughts and emotions, negative or positive, deeply characterizes us and is part of the mechanisms of defence that situations perceived as painful or potentially dangerous trigger in us, without us even realizing it. We could say that the way we relate to what is different, foreign, unknown[3] tells us more about ourselves, about our temper, than about the others: “Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves”[4]. The others, in short, act as a mirror that sends back information about us which, if we were willing to grasp it, could enlighten us as much on our strengths as on our weaknesses. What we do not like in others, which does not correspond to our expectations or our values, could actually enrich our experience through the opportunity to know and understand what about us would otherwise remain hidden… even to ourselves[5].

In general – unless there are life or death issues at stake – we are unwilling to risk the loss of the routine and question the picture we wish to match, because this would mean to undermine the system of values we use to orientate ourselves in our lives. We hold on tight to our… plank: “How can you say to your brother, ‘Brother, let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when you yourself fail to see the plank in your own eye?” (Luke 6:42). The presence of the other among us causes us to “work” on a widespread prejudice: that there is a primary culture at the beginning, a single culture (one’s own!) that can serve as a common base for identity. So, would the different cultures that meet in the world be only variations of one’s own?

question the picture we wish to match, because this would mean to undermine the system of values we use to orientate ourselves in our lives. We hold on tight to our… plank: “How can you say to your brother, ‘Brother, let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when you yourself fail to see the plank in your own eye?” (Luke 6:42). The presence of the other among us causes us to “work” on a widespread prejudice: that there is a primary culture at the beginning, a single culture (one’s own!) that can serve as a common base for identity. So, would the different cultures that meet in the world be only variations of one’s own?

In truth, in the encounter with the other we find similarities and differences and we find ourselves experiencing that the former bring us closer and reassure us, while the latter separate and disturb us, so we tend to “discard” them. Therefore, to believe that “unity always comes with diversity”[6] perhaps means to work on the relationship between different people, valuing also and above all what we would “discard”. The so-called culture of encounter commits us, as Pope Francis tirelessly urges us, to “come out of ourselves and set out on pilgrimage”[7]. The comparison with the other, far from being taken for granted, requires everyone not to underestimate the concept of difference and its implications. It is a matter of learning to bear and assimilate – within the inevitable timeframes and struggles, both personal and collective – the irruption of unpleasant and disturbing feelings of vulnerability, of non-sufficiency of oneself and of one’s own belonging.

Instead, to oppose the current culture that sees the discard as something to be eliminated and pushes to cancel differences would open “the ways to resume the threads of an often partial or deformed relationship with the truth, with other human beings and with oneself”[8], as well as with the Earth that hosts everyone. Part of what we need for our growth is to be found in the very people who annoy us the most!

“Man is created in such a way that he is first of all given to himself in a ‘starter form’; open and prepared for what will come to him.

“Man is created in such a way that he is first of all given to himself in a ‘starter form’; open and prepared for what will come to him.

If he gets stuck or stiffened, if he remains closed in himself, if he never takes the risk of being in an attitude of dedication to reality, then he will become ever more rigid and miserable.

He has kept his soul for himself and thus has lost it more and more”[9].

The difference is the first characteristic of people and of their individuality where each one is both a universe and unique, like the identities that have matured and were determined in human communities throughout history. Difference puts us in contact with peoples, ethnicities, groups and minorities who are bearers, precisely, of their own culture, of the original civilization, in the expressions and inflections of their language of origin, of their own vision of the world impregnated of the meaning of art, thought, creativity, in which the plurality of cultures of the human race is summed up: “You, in fact, of whatever condition or nation you are, man or woman, you all have the same eyes. But your different look has seen different things”[10].

“If you are different, you will have something new and true to say. And not words to repeat. The difference will provide you with the meaning of things and men. If similarity will invite you to sit beside her, difference will call you to meet her, laying her eyes in yours, in front of you, who are not everything, but only a piece of life to live with others”[11].

How, then, can we experience diversity not as an obstacle to overcome, a discomfort to eliminate, but as an essential resource, the privileged clue to a whole series of treasures, peculiarities, prerogatives and characters that are waiting to be acknowledged and valued in order to prevent diversity from turning into social and civil, juridical and economic inequalities? How can we prevent diversity from leading to fragmentation and violence?

How can we avoid escaping the encounter with the other, which is destabilizing and life-giving? What is more, how  we welcome the other integrally, that is, both with his similarities and his differences? How can we learn to listen to the different and to know how to respond to him when he calls us with his look, with his invitation: “Welcome me!”[12].

we welcome the other integrally, that is, both with his similarities and his differences? How can we learn to listen to the different and to know how to respond to him when he calls us with his look, with his invitation: “Welcome me!”[12].

We walk on a ground of questioning, experimentation and innovation:“doubts and loves dig up the world” …says the poet[13].

(Part one)

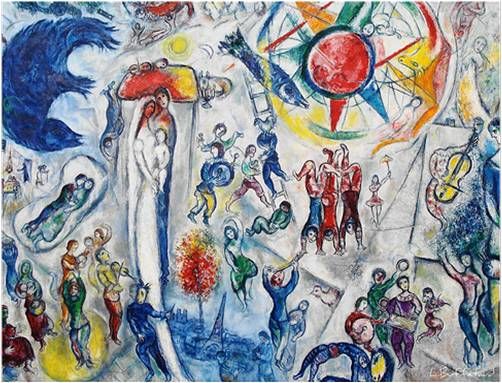

Marc Chagall, The life, 1911-1912

[1] See Maria Zambrano (1904-1991), Spanish philosopher in Towards a knowledge of the soul, 1991.

[2] See Declaration of the 30th Congregational Chapter.

[3] It is no coincidence that in the homepage we have chosen to give space to the invitation that the Congregation Leader, Sister Ellen Kelly, following her participation in a meeting of our Italy-Malta Unit in March 2016, addressed to the sisters and lay partners engaged in the mission: “Find the courage to move forward. God will meet us while we walk towards the future.”

[4] Carl Gustav Jung

[5] See Julia Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves, 1990

[6] We have already recalled this concept in January’s editorial about Peace: it was expressed by Pope Francis in his meeting with 17 religious leaders from Myanmar, Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, Catholics and Christians from other confessions. On 28/11/2017.

[7] Evangelii Gaudium 124

[8] See Agostino Giovagnoli, L’Umanesimo di Papa Francesco. Per una cultura dell’incontro, 2015

[9] See Romano Guardini (1885-1968), an Italian-German theologian and writer, who tried to apply the Christian vision of the world to all aspects of culture, from poetry to music, from technology to philosophy without ever disregarding the consideration of the individual and his freedom. He longed for an “awakening of the Church of souls”.

[10] Idem

[11] See Renato Zilio, Elogio della differenza, 1995

[12] Placido Sgroi in Teologia dell’ospitalità, 2019, on page 83, suggests that “we can interpret the evocative passage of Revelation 3:20: ‘Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me’.”

[13] See the poem “The place where we are right” by the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. He is considered by many to be the greatest modern Israeli poet, a convinced advocate of peace and reconciliation in Palestine. In this poem, love is seen as a fruit that grows in an “area” of uncertainty, half empty, as do thought, creativity and the ability to doubt. The place where we are right was part of the “weave of Word and Words” that inspired the XXX General Chapter 2015 and that we have also included in the poetic itinerary of the #gratiagreta initiative, in line with the pattern of values that Yehuda Amichai tries to weave to nourish life in times and places of denied and/or suffocated conflicts, to the detriment of the weakest and “discarded”: justice, reconciliation and, above all, mercy, that is, in Yehuda Amichai’s lay language, love.

(prima parte)

Marc Chagall, La vita, 1911-1912

[1] Cfr.Maria Zambrano (1904-1991), filosofa spagnola in Verso un sapere dell’anima, 1991.

[2] Dalla Dichiarazione del 30° Capitolo di Congregazione.

[3] Non a caso nella Home abbiamo scelto di dare risalto all’invito che la Responsabile di Congregazione, Suor Ellen Kelly, a seguito della sua partecipazione ad un incontro della nostra Unità Italia-Malta, a marzo 2016, a rivolto, alle Sorelle e ai Partners laici impegnati nella missione: “Abbiate il coraggio di andare di andare avanti. Dio ci viene incontro mentre camminiamo verso il futuro”.

[4] Carl Gustav Jung

[5] Cfr. Julia Kristeva, Stranieri a sé sessi, 1990

[6] È un concetto che abbiamo già ricordato nell’editoriale del mese di gennaio sulla Pace: è stato espresso da Papa Francesco nell’incontro con 17 leader religiosi del Myanmar, buddisti, islamici, indù, ebrei, cattolici e cristiani di altre confessioni. Il 28/11/2017.

[7] Evangelii Gaudium 124

[8] Cfr Agostino Giovagnoli, L’Umanesimo di Papa Francesco. Per una cultura dell’incontro, 2015

[9] Cfr. Romano Guardini (1885-1968) teologo e scrittore italo-tedesco, cercò di applicare la visione cristiana del mondo a tutti gli aspetti della cultura, dalla poesia alla musica, dalla tecnica alla filosofia senza mai prescindere mai dalla considerazione dell’individuo e della sua libertà. Guardava ad un «risveglio della Chiesa delle anime».

[10]Cfr. idem

[11] Cfr. Renato Zilio, Elogio della differenza, 1995

[12] Placido Sgroi in Teologia dell’ospitalità, 2019, a pag.83, suggerisce che “possiamo interpretare il suggestivo passo di Apocalisse 3,20: ‘Ecco, io sto alla porta e busso: se qualcuno ascolta la mia voce e mi apre la porta, io entrerò da lui e cenerò con lui ed egli con me.”

[13] Cfr .il poema “Da dove abbiamo ragione” del poeta israeliano Yuhuda Amichai. Egli è considerato da molti il più grande poeta israeliano moderno, convinto fautore della pace e della riconciliazione in Palestina. In questo poema l’amore viene visto come un frutto che cresce in “zona” di incertezza, di mezzo vuoto, così come il pensiero, la creatività e la capacità di dubitare. Da dove abbiamo ragione ha fatto parte della” trama di Parola e di parole” che ha ispirato il XXX Capitolo Generale 2015 e che abbiamo inserito anche nel Percorso poetico dell’iniziativa #gratiagreta, in sintonia con la trama di valori che Yehuda Amichai prova a tessere per nutrire la vita in tempi e luoghi di conflitti negati e/o soffocati, a danno dei più deboli e “scartati”: la giustizia, la riconciliazione e, soprattutto, la misericordia, cioè, nel linguaggio laico di Yehuda Amichai, l’amore.